Not able to visit us in person? Below are 360-degree virtual tours of our exhibits from the comfort of your home or classroom. Stayed tuned as we upload new tours each semester.

Tips: Use your mouse to look around and move through the tour. Click the labels to view more information about each item in the exhibit. For fullscreen mode, click the bottom right arrows to expand the window.

First Farmers of the Barren River Valley

Click here to view in a new window.

Styles &thegistofit

Use the arrows to move around the exhibit.

Click the label markers for more information.

Mary Sloss McCormick (1863-1904) in a dress made by the Taylor Company,

circa 1889. The dress has a velvet top with large buttons and a silk skirt with

ribbons. It may have been part of her wedding trousseau, given that the

formal portrait was taken the same year as Mary’s wedding to Hershel P.

McCormick.

Afternoon dress, 1892

Worn by Martha Florence Beard

This “going away gown” was part of Martha Florence Beard's trousseau

for her marriage to Charles Claudius Russell. The bodice and skirt are

made with gray ground foulard silk, printed in a stylized design. Bodice

is trimmed with a beige high standing lace collar and cuffs. It features

rows of metal beads and sequins, brown and gold novelty ribbon, small

shoulder puffs, and self-fabric ruffles on the skirt hem. Mrs. A.H. Taylor

Company label printed inside on the bodice petersham.

Donated by Margaret Cross. Co-adopted by Herbert H. Beckwith

and Bill and Joey Powell. KM4878/1955.16.1

Use the arrows to move around the exhibit.

Click the label markers for more information.

Mary Sloss McCormick (1863-1904) in a dress made by the Taylor Company,

circa 1889. The dress has a velvet top with large buttons and a silk skirt with

ribbons. It may have been part of her wedding trousseau, given that the

formal portrait was taken the same year as Mary’s wedding to Hershel P.

McCormick.

Afternoon dress, 1892

Worn by Martha Florence Beard

This “going away gown” was part of Martha Florence Beard's trousseau

for her marriage to Charles Claudius Russell. The bodice and skirt are

made with gray ground foulard silk, printed in a stylized design. Bodice

is trimmed with a beige high standing lace collar and cuffs. It features

rows of metal beads and sequins, brown and gold novelty ribbon, small

shoulder puffs, and self-fabric ruffles on the skirt hem. Mrs. A.H. Taylor

Company label printed inside on the bodice petersham.

Donated by Margaret Cross. Co-adopted by Herbert H. Beckwith

and Bill and Joey Powell. KM4878/1955.16.1

Carrie Burnam as a child, seated with her older brother, Tom, who died at the age of 7 from cholera.

Photograph provided by Lynn Gazis, Carrie’s great-great-granddaughter.

Nelle Gooch Travelstead in her wedding gown, designed by Mrs.

A. H. Taylor Company, 1906. Nelle attended Potter College at age

17, and eventually earned her A.B. in Education from the Western

Kentucky State Normal School and an M.A. from Columbia University.

Carrie Burnam as a child, seated with her older brother, Tom, who died at the age of 7 from cholera.

Photograph provided by Lynn Gazis, Carrie’s great-great-granddaughter.

Nelle Gooch Travelstead in her wedding gown, designed by Mrs.

A. H. Taylor Company, 1906. Nelle attended Potter College at age

17, and eventually earned her A.B. in Education from the Western

Kentucky State Normal School and an M.A. from Columbia University.

"According to my mother, [Carrie] began designing dresses for her Potter College friends,

who later carried her reputation throughout the South, where small town stores could not

supply fashionable ladies clothing. My grandmother was never a seamstress. She began

as a dress designer and always hired other persons to make the dresses."

- Burnam P. Beckwith

Elizabeth Avery "Bessie" Taft, a 1907 graduate from Houston, Texas,

and her mother were accustomed to purchasing so many dresses, coats,

suits, and opera cloaks that Bessie's father claimed she had attended

Potter College only to be closer to Mrs. Taylor's establishment.

- Janice Faye Walker Centers in "A Kentucky Dressmaker" (Thesis, WKU, 1977)

"The location of the Mrs. A. H. Taylor Company and the Sumpter Sisters...

has had a great influence on local styles, and has contributed largely to the

reputation of the city as a shopping center..." - Park City Daily News, April 1917.

Evening jacket, ca. 1915 Worn by Nora McGee (1883-1967)

This tangerine velvet cocoon jacket features a large shawl-like collar

with center front tie and is lined with ivory crepe. It has covered

cording details on the collar, arms, and back. Influential French

designer Paul Poiret inspired Edwardian cocoon jackets of luxurious

materials such as velvet and fur. Donated by Mrs. Henry Thomas

Hagerman.

Adopted by JoNell Hester. KM4895/1965.2.15.

Afternoon dress, 1903

Worn by Corinne Ayres (1875-1945)

The high neck bodice is made with printed pink ground silk satin with

Art Nouveau-inspired design of white, green, and yellow. Plastron front

of off-white net, bodice and sleeves trimmed with off-white silk twill and

beige lace with a standing collar and long sleeves. It features a label from

the Mrs. A.H. Taylor Company on interior petersham. The skirt is trimmed

with self-fabric inset pleated sections and beige lace with train.

Completed with pink cotton and silk petticoat. Corinne attended Potter

College around 1894.

Donated by Mrs. Howard Compton. Adopted by JoNell Hester.

KM2014.21.1

Hattie Strange Claggett (1872-1963) wearing her Bowling Green Fair

Hop evening gown, which was made by the Taylor Company. The

woman on the right is an unidentified friend or family member.

Evening coat, 1906 Worn by Nelle Gooch Travelstead (1888-1974)

This loose-fitted three-quarter-length coat cut in simple style lines with large

pagoda sleeves was created with ecru wool broadcloth and lined in silk crepe

de chine and is self-closing. The neck, front, and sleeve areas are embellished

with fine Brussels lace in a flower and vine design. The flourish of lace on the

neckline extends midway down the front of the coat. Franklin, KY native and

Potter College graduate Nelle Gooch likely had this coat made as part of her

1906 wedding trousseau.

Donated by Nelle Gooch Travelstead. Adopted by Beth Hester.

KM5716/1967.15.1

Skirt, ca. 1898.

Worn by Bettie Robertson Hagerman (1867-1926) This moiré a-line style

skirt is part of a two-piece satin and velvet dress (bodice not exhibited).

Trimmed with pink silk ribbons at the hem.

Donated by Mrs. Henry Thomas Hagerman. Available for Adoption.

KM2825/1948.11.1

"According to my mother, [Carrie] began designing dresses for her Potter College friends,

who later carried her reputation throughout the South, where small town stores could not

supply fashionable ladies clothing. My grandmother was never a seamstress. She began

as a dress designer and always hired other persons to make the dresses."

- Burnam P. Beckwith

Elizabeth Avery "Bessie" Taft, a 1907 graduate from Houston, Texas,

and her mother were accustomed to purchasing so many dresses, coats,

suits, and opera cloaks that Bessie's father claimed she had attended

Potter College only to be closer to Mrs. Taylor's establishment.

- Janice Faye Walker Centers in "A Kentucky Dressmaker" (Thesis, WKU, 1977)

"The location of the Mrs. A. H. Taylor Company and the Sumpter Sisters...

has had a great influence on local styles, and has contributed largely to the

reputation of the city as a shopping center..." - Park City Daily News, April 1917.

Evening jacket, ca. 1915 Worn by Nora McGee (1883-1967)

This tangerine velvet cocoon jacket features a large shawl-like collar

with center front tie and is lined with ivory crepe. It has covered

cording details on the collar, arms, and back. Influential French

designer Paul Poiret inspired Edwardian cocoon jackets of luxurious

materials such as velvet and fur. Donated by Mrs. Henry Thomas

Hagerman.

Adopted by JoNell Hester. KM4895/1965.2.15.

Afternoon dress, 1903

Worn by Corinne Ayres (1875-1945)

The high neck bodice is made with printed pink ground silk satin with

Art Nouveau-inspired design of white, green, and yellow. Plastron front

of off-white net, bodice and sleeves trimmed with off-white silk twill and

beige lace with a standing collar and long sleeves. It features a label from

the Mrs. A.H. Taylor Company on interior petersham. The skirt is trimmed

with self-fabric inset pleated sections and beige lace with train.

Completed with pink cotton and silk petticoat. Corinne attended Potter

College around 1894.

Donated by Mrs. Howard Compton. Adopted by JoNell Hester.

KM2014.21.1

Hattie Strange Claggett (1872-1963) wearing her Bowling Green Fair

Hop evening gown, which was made by the Taylor Company. The

woman on the right is an unidentified friend or family member.

Evening coat, 1906 Worn by Nelle Gooch Travelstead (1888-1974)

This loose-fitted three-quarter-length coat cut in simple style lines with large

pagoda sleeves was created with ecru wool broadcloth and lined in silk crepe

de chine and is self-closing. The neck, front, and sleeve areas are embellished

with fine Brussels lace in a flower and vine design. The flourish of lace on the

neckline extends midway down the front of the coat. Franklin, KY native and

Potter College graduate Nelle Gooch likely had this coat made as part of her

1906 wedding trousseau.

Donated by Nelle Gooch Travelstead. Adopted by Beth Hester.

KM5716/1967.15.1

Skirt, ca. 1898.

Worn by Bettie Robertson Hagerman (1867-1926) This moiré a-line style

skirt is part of a two-piece satin and velvet dress (bodice not exhibited).

Trimmed with pink silk ribbons at the hem.

Donated by Mrs. Henry Thomas Hagerman. Available for Adoption.

KM2825/1948.11.1

"According to my mother, [Carrie] began designing dresses for her Potter College friends,

who later carried her reputation throughout the South, where small town stores could not

supply fashionable ladies clothing. My grandmother was never a seamstress. She began

as a dress designer and always hired other persons to make the dresses."

- Burnam P. Beckwith

Elizabeth Avery "Bessie" Taft, a 1907 graduate from Houston, Texas,

and her mother were accustomed to purchasing so many dresses, coats,

suits, and opera cloaks that Bessie's father claimed she had attended

Potter College only to be closer to Mrs. Taylor's establishment.

- Janice Faye Walker Centers in "A Kentucky Dressmaker" (Thesis, WKU, 1977)

"The location of the Mrs. A. H. Taylor Company and the Sumpter Sisters...

has had a great influence on local styles, and has contributed largely to the

reputation of the city as a shopping center..." - Park City Daily News, April 1917.

Evening jacket, ca. 1915 Worn by Nora McGee (1883-1967)

This tangerine velvet cocoon jacket features a large shawl-like collar

with center front tie and is lined with ivory crepe. It has covered

cording details on the collar, arms, and back. Influential French

designer Paul Poiret inspired Edwardian cocoon jackets of luxurious

materials such as velvet and fur. Donated by Mrs. Henry Thomas

Hagerman.

Adopted by JoNell Hester. KM4895/1965.2.15.

Afternoon dress, 1903

Worn by Corinne Ayres (1875-1945)

The high neck bodice is made with printed pink ground silk satin with

Art Nouveau-inspired design of white, green, and yellow. Plastron front

of off-white net, bodice and sleeves trimmed with off-white silk twill and

beige lace with a standing collar and long sleeves. It features a label from

the Mrs. A.H. Taylor Company on interior petersham. The skirt is trimmed

with self-fabric inset pleated sections and beige lace with train.

Completed with pink cotton and silk petticoat. Corinne attended Potter

College around 1894.

Donated by Mrs. Howard Compton. Adopted by JoNell Hester.

KM2014.21.1

Hattie Strange Claggett (1872-1963) wearing her Bowling Green Fair

Hop evening gown, which was made by the Taylor Company. The

woman on the right is an unidentified friend or family member.

Evening coat, 1906 Worn by Nelle Gooch Travelstead (1888-1974)

This loose-fitted three-quarter-length coat cut in simple style lines with large

pagoda sleeves was created with ecru wool broadcloth and lined in silk crepe

de chine and is self-closing. The neck, front, and sleeve areas are embellished

with fine Brussels lace in a flower and vine design. The flourish of lace on the

neckline extends midway down the front of the coat. Franklin, KY native and

Potter College graduate Nelle Gooch likely had this coat made as part of her

1906 wedding trousseau.

Donated by Nelle Gooch Travelstead. Adopted by Beth Hester.

KM5716/1967.15.1

Skirt, ca. 1898.

Worn by Bettie Robertson Hagerman (1867-1926) This moiré a-line style

skirt is part of a two-piece satin and velvet dress (bodice not exhibited).

Trimmed with pink silk ribbons at the hem.

Donated by Mrs. Henry Thomas Hagerman. Available for Adoption.

KM2825/1948.11.1

Bowling Green Postman, circa 1910,overloaded with many packages.

One of the packages is addressed to the Mrs. A. H. Taylor Company.

"What a joy! When you tried on your dress there was nothing to do.

Nothing to be lengthened - nothing to be tightened. Every hook and eye

was in place. When Mrs. Taylor made you a dress, she made you a dress!"

- Kate Duncan

Afternoon dress, 1903

Worn by Corinne Ayres (1875-1945)

The high neck bodice is made with printed pink ground silk satin with

Art Nouveau-inspired design of white, green, and yellow. Plastron front

of off-white net, bodice and sleeves trimmed with off-white silk twill and

beige lace with a standing collar and long sleeves. It features a label from

the Mrs. A.H. Taylor Company on interior petersham. The skirt is trimmed

with self-fabric inset pleated sections and beige lace with train.

Completed with pink cotton and silk petticoat. Corinne attended Potter

College around 1894.

Donated by Mrs. Howard Compton. Adopted by JoNell Hester.

KM2014.21.1

Bowling Green Postman, circa 1910,overloaded with many packages.

One of the packages is addressed to the Mrs. A. H. Taylor Company.

"What a joy! When you tried on your dress there was nothing to do.

Nothing to be lengthened - nothing to be tightened. Every hook and eye

was in place. When Mrs. Taylor made you a dress, she made you a dress!"

- Kate Duncan

Afternoon dress, 1903

Worn by Corinne Ayres (1875-1945)

The high neck bodice is made with printed pink ground silk satin with

Art Nouveau-inspired design of white, green, and yellow. Plastron front

of off-white net, bodice and sleeves trimmed with off-white silk twill and

beige lace with a standing collar and long sleeves. It features a label from

the Mrs. A.H. Taylor Company on interior petersham. The skirt is trimmed

with self-fabric inset pleated sections and beige lace with train.

Completed with pink cotton and silk petticoat. Corinne attended Potter

College around 1894.

Donated by Mrs. Howard Compton. Adopted by JoNell Hester.

KM2014.21.1

Unfinished Log Cabin variation quilt top, circa 1907, created from

discarded fabric samples from Taylor’s factory. This quilt is attributed to

Frances Clarke Matlock (1834-1917) and was used by the family for years.

Dinner dress, ca. 1916.

Worn by Eleanor May Heriges Denhardt (1886-1977)

This dress illustrates how silhouettes had evolved from the cinched corseted waist of

the fourth quarter of the nineteenth century to the more tubular style indicative of

the 1910s. While the bodice and skirt are made of black silk faille (a plain-woven silk/

cotton blend), the underbodice is constructed of black silk satin-faced organza.

Trimmed with black jet beading, a silk satin belt, and black cotton net cuff ruffles.

Donated by Mrs. J.G. Denhardt. Adopted by JoNell Hester. KM4776

Unfinished Log Cabin variation quilt top, circa 1907, created from

discarded fabric samples from Taylor’s factory. This quilt is attributed to

Frances Clarke Matlock (1834-1917) and was used by the family for years.

Dinner dress, ca. 1916.

Worn by Eleanor May Heriges Denhardt (1886-1977)

This dress illustrates how silhouettes had evolved from the cinched corseted waist of

the fourth quarter of the nineteenth century to the more tubular style indicative of

the 1910s. While the bodice and skirt are made of black silk faille (a plain-woven silk/

cotton blend), the underbodice is constructed of black silk satin-faced organza.

Trimmed with black jet beading, a silk satin belt, and black cotton net cuff ruffles.

Donated by Mrs. J.G. Denhardt. Adopted by JoNell Hester. KM4776

Unfinished Log Cabin variation quilt top, circa 1907, created from

discarded fabric samples from Taylor’s factory. This quilt is attributed to

Frances Clarke Matlock (1834-1917) and was used by the family for years.

Dinner dress, ca. 1916.

Worn by Eleanor May Heriges Denhardt (1886-1977)

This dress illustrates how silhouettes had evolved from the cinched corseted waist of

the fourth quarter of the nineteenth century to the more tubular style indicative of

the 1910s. While the bodice and skirt are made of black silk faille (a plain-woven silk/

cotton blend), the underbodice is constructed of black silk satin-faced organza.

Trimmed with black jet beading, a silk satin belt, and black cotton net cuff ruffles.

Donated by Mrs. J.G. Denhardt. Adopted by JoNell Hester. KM4776

“A La Sprite” corset with thirty-two whale bone stays, a silk covering,

and silk lace, circa 1904.Worn by Ibbie Beard Allen (1864–1958).

When she used to get kinda upset and she'd start her dentures clicking (pop, pop, pop)

you could hear her from one end of the building to the other. She would purse up those

lips and stomp up those stairs and fold her arms. She'd get after you for nothing then,

so we'd all quiet down and pass it along. 'The boss is on a rampage!' - Zelma Wilkerson

Doll Clothes created with scraps of discarded fabric from Taylor’s factory.

George Anna Hobson Duncan(1907-1988) remembered visiting the factory

as a child with her mother and being given scraps of “luxurious materials” to

construct doll dresses, stating, “Carrie allowed any youngsters who came

into the store to choose material from a bin of scraps and trimmings to be

made into doll clothing.”

Pins, pins, pins! Jane Morningstar remembered playing with discarded

pins from the Taylor company, stating, “My brothers collected the pins.

They tossed the pins out. I don’t know why in particular; maybe they

dropped them on the floor and swept them out. They would collect the

pins and we would use them as barter in our play and games.”

Group of Bowling Green, KY, women, in 1902, likely employees of the Taylor

Company. Carrie is the woman wearing a black tie and pin at her neck, front center.

Others identified in the photograph are Blanche (Jamison) Potter,[Elizabeth] Lite

(Motley) Adams, Mattie (Burnam) Hines, Lelia Gossom Downer, Mamie (Anderson) Barr,

Dixie (Robinson)Mayo, Lizzie (Coombs) Porter, Annie Hines, and Elizabeth(Valentine)

Matlock.

Wedding dress bodice, ca. 1898

Worn by Myrtle Vass Jackson (1874-1975)

This off-white cotton organdy bodice is trimmed with a decorative cross-tucked,

self-fabric yoke, yoke ruffles edged with lace, and a ruched silk satin ribbon.

Waist-length, it has long sleeves and a high neck. (Matching skirt not exhibited).

Donated by Douglas Bradford. Available for Adoption. KM1985.82.1

Bodice, 1899

Worn by Elizabeth Lucy Snow Ansley (1848-1905), Howard County, AR

Black striped silk bodice trimmed with lace. Interior label Mrs. A. H. Taylor & Co.

According to Ansley’s granddaughter, her grandmother’s family “always went to

Kentucky to get their ‘good’ clothes made.”

Donated by William Utterback. Adopted by Beth Hester. 1986.26.1

“A La Sprite” corset with thirty-two whale bone stays, a silk covering,

and silk lace, circa 1904.Worn by Ibbie Beard Allen (1864–1958).

When she used to get kinda upset and she'd start her dentures clicking (pop, pop, pop)

you could hear her from one end of the building to the other. She would purse up those

lips and stomp up those stairs and fold her arms. She'd get after you for nothing then,

so we'd all quiet down and pass it along. 'The boss is on a rampage!' - Zelma Wilkerson

Doll Clothes created with scraps of discarded fabric from Taylor’s factory.

George Anna Hobson Duncan(1907-1988) remembered visiting the factory

as a child with her mother and being given scraps of “luxurious materials” to

construct doll dresses, stating, “Carrie allowed any youngsters who came

into the store to choose material from a bin of scraps and trimmings to be

made into doll clothing.”

Pins, pins, pins! Jane Morningstar remembered playing with discarded

pins from the Taylor company, stating, “My brothers collected the pins.

They tossed the pins out. I don’t know why in particular; maybe they

dropped them on the floor and swept them out. They would collect the

pins and we would use them as barter in our play and games.”

Group of Bowling Green, KY, women, in 1902, likely employees of the Taylor

Company. Carrie is the woman wearing a black tie and pin at her neck, front center.

Others identified in the photograph are Blanche (Jamison) Potter,[Elizabeth] Lite

(Motley) Adams, Mattie (Burnam) Hines, Lelia Gossom Downer, Mamie (Anderson) Barr,

Dixie (Robinson)Mayo, Lizzie (Coombs) Porter, Annie Hines, and Elizabeth(Valentine)

Matlock.

Wedding dress bodice, ca. 1898

Worn by Myrtle Vass Jackson (1874-1975)

This off-white cotton organdy bodice is trimmed with a decorative cross-tucked,

self-fabric yoke, yoke ruffles edged with lace, and a ruched silk satin ribbon.

Waist-length, it has long sleeves and a high neck. (Matching skirt not exhibited).

Donated by Douglas Bradford. Available for Adoption. KM1985.82.1

Bodice, 1899

Worn by Elizabeth Lucy Snow Ansley (1848-1905), Howard County, AR

Black striped silk bodice trimmed with lace. Interior label Mrs. A. H. Taylor & Co.

According to Ansley’s granddaughter, her grandmother’s family “always went to

Kentucky to get their ‘good’ clothes made.”

Donated by William Utterback. Adopted by Beth Hester. 1986.26.1

Hats were standard items in most women's wardrobes. This toque-style hat

which resembles a ship's prow about to launch was briefly in fashion from

1903 to 1905. Donated by WKU IDFM program.

White cotton ladies drawers or pantaloons with embroidered trim and a

thick ribbon for closure. Date unknown. Donated by Kate Clagett Duncan.

"She is a living example...that initiative, courage, and ability will win

success in large measure in a small town just as easily as it will in a

large city." - Courier Journal, October 20, 1912.

Petticoat of fine white muslin with lace trim and inserts and a ribbon drawn

through the lace. Purchased at the Taylor Company as part of Nelle Gooch’s

wedding trousseau in 1906.

Chemise of white muslin with holes or large eyelets around the neckline for a

ribbon or cord and floral and ribbon motif machine embroidery. Reportedly

purchased at the Taylor Company as part of Nelle Gooch’s wedding trousseau

in 1906.

Hatpins of varying sizes were utilized. Designs include those shown here,

such as large ball-shaped glass heads, violet cut glass, and engraved gems.

Others featured more ornate designs, such as engraved gold leaves or the

Egyptian-influenced scarab beetle design.

Fans also came in a variety of styles, typically utilizing feathers. Popular

from the1880s to 1910, they were considered a year-round accessory. This

peacock fan features a woven handle and was donated as part of the

Calvert Family estate of Bowling Green, KY.

Women could choose from a variety of purse styles when accessorizing their

look. Worked using fine linen, cotton and silk threads, dainty Irish crochet

purses were the perfect accessory for the fine white cotton and linen dresses

popularly known today as lingerie dresses.

The small metal purse in this case is a chatelaine purse. Worn hooked onto

the wearer's belt, its elegant frame exhibits the free flowing, organic elements

of the Art Nouveau style. Made by Whiting & Davis Company of Massachusetts.

Donated by Ella Campbell.

Click here to view in a new window.

Gazing Deeply: The Art and Science of Mammoth Cave

Moccasins found in Salt Cave, now part of Mammoth Cave.

These moccasins were likely worn by Native Americans who mined

the cave for its gypsum formations.

According to a 1973 letter from Roy H. Owsley, the moccasins were found by Andy Collins

(brother of Floyd Collins), Gabrielle Robertson, Cecil Wright, and Roy during a trip to Salts

Cave in Hart County in the mid-1920s. Owsley stated,

"Our second trip into the cave lasted several hours. During this trip, the three of us (Andy

Collins, Cecil Wright and I) explored several branches off of the main cavern, and in one of

these in particular we found names and dates that had been scratched on the walls of the

cave with a knife.... In this same chamber...we found several Indian moccasins that were

almost perfectly preserved, along with some other lesser items, all of which were very

carefully carried and handled by Cecil and me..."

Geological Specimens.

Courtesy WKU Department of Geology and Geography.

Minerals of Mammoth Cave

Madison Whittle, Visual Arts Major, Fall 2019.

This work depicts a scientific collection of a few of the minerals found in Mammoth cave.

Accompanying each realistic illustration is the respective crystal system, or a category classified

by possible relations of the crystal axes. The following minerals are featured:

A. Aragonite (orthorhombic)

B. Pyrite (cubic)

C. Gypsum flower (monoclinic)

D. Celestine (orthorhombic)

E. Mirabilite (monoclinic)

"Rosa's Bower" by Charles Waldack, 1866.

Depicts part of the roof in Cleveland's Cabinet, featuring gypsum flowers resembling

roses and dahlia.

Courtesy WKU Library Special Collections.

Geological Specimens.

Courtesy WKU Department of Geology and Geography.

"The Altar" by Charles Waldack, 1866.

This cluster of columns is so named due to marriages which took place in this part of the cave.

Courtesy WKU Library Special Collections.

Stalactite and Stalagmite formations, taken by H. C. Ganter and Carlos G. Darnall, 1889.

Courtesy WKU Library Special Collections.

Echo River Tour, from glass plate negative by H. C. Ganter and Carlos G. Darnall, 1889.

Courtesy WKU Library Special Collections.

Stalactite and Stalagmite formations, print from glass plate negative by H. C. Ganter

and Carlos G. Darnall, 1889.

Courtesy WKU Library and Special Collections.

"Cliffs over the Dead Sea" stereoview, taken by Charles Waldock, 1866.

Courtesy WKU Library and Special Collections.

Experiments at Mammoth Cave.

Courtesy Crawford Hydrology Lab.

Carte-de-visite photograph of Esther Virginia "Jennie" Ray Younglove in a caving outfit.

Courtesy WKU Library special collections.

Grease oil lamp made with tin and copper, used in the explorations of Mammoth Cave, n.d.

Kentucky Museum

1847 journal of a trip through Kentucky and Visit to Mammoth Cave.

Courtesy WKU Library Special Collections

Anna Harris begins an 80-foot rappel into a pit in Great Onyx Cave to collect

underground river samples.

Courtesy Crawford Hydrology Lab.

Jumar

This yellow device is a "jumar" and is an example of the types of climbing equipment used to

travel through the park's caves. Mammoth Cave has many vertical shafts, some more than 150

feet deep, that require special equipment. On loan from Dr. Chris Groves.

Price AA Current Meter

Used to measure flow rates of surface and underground rivers. On loan from Dr. Chris Groves.

Cavers preparing to assist park research efforts by exploring and mapping an

underground stream.

Courtesy Crawford Hydrology Lab.

Pygmy Style Current Meter

This tiny "pygmy" style meter is used to measure flow rates of small streams.

On loan from Dr. Chris Groves.

Helmet with Light

Helmets and lights are among the most important pieces of equipment that cave scientists

and explorers use. On loan from Dr. Chris Groves.

Rite in the Rain notepad

It is important to take careful notes when collecting data, whether above or below ground.

"Rite in the Rain" paper is waterproof, and mud can even be washed off without smearing notes.

On loan from Dr. Chris Groves.

Timeline starts here. Hover to see!

Paleoindian ~ 11,500 BP to 10,000 BP

There was little habitation in the Mammoth Cave area

at this time. The few tools found from that period may

have been brought in from elsewhere.

Archaic ~ 10,000 BP to 3,000 BP

The first explorers entered the cave about

4,700 years ago. Extensive mineral mining in

the cave began about 1,500 years later.

Woodland ~ 3,000 BP to 900 AD

The deepest ancient cave exploration known anywhere

in the world took people up to 5 miles from the nearest

entrance. Major cave exploration ended about

2,200 years ago.

Mississippian ~ 900 AD to 1500 AD

and Proto-Historic ~ 1500 AD to 1700 AD

There was regional habitation, but no deep cave

exploration; some caves were used for rock art.

Early Exploration ~ 1790s to 1940s

Early saltpeter mining gave way to tours starting in 1815.

Stephen Bishop made major discoveries in the 1830s, and

German engineer Max Kamper made an accurate map of

35 miles of passages in 1908.

C-3 Expedition ~ 1940s to 1957

Independent explorers discovered a huge cave

system beneath Flint Ridge. The 1954 Floyd Collins

Crystal Cave (C-3) Expedition by the National

Speleological Society nurtured a new era of

sustained, organized exploration.

Cave Research Foundation ~ 1957 to Present

The National Park Service and newly-formed Cave

Research Foundation agreed to collaborate in

exploration and scientific study. Flint Ridge and

Mammoth were connected in 1972, at that time

the world’s longest cave at 144 miles.

Roppel Cave ~ 1976 to Present

Nearly 50 miles were explored in Roppel Cave

after its discovery in 1976. The Mammoth-Roppel

connection in 1983 made a cave system then

almost 300 miles long.

Fisher Ridge Cave ~ 1982 to Present

Fisher Ridge Cave was discovered in 1981.

Currently the world’s 10th longest cave, it may

connect to Mammoth one day. In the 1980s,

cavers working for hydrologist Jim Quinlan

mapped many miles of underground rivers.

Collaborative Exploration ~ 1992 to Present

Historic collaboration by explorers resulted in the

1992 map “Caves of the Dripping Springs Escarpment.”

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) technology

matured for cave survey data management.

691.7 miles

As of January 2020, there are 697.1 miles of cave

passages documented beneath Hart, Barren and

Edmonson Counties.

Timeline developed by Dr. Chris Groves in partnership

with Dr. George M. Crothers, Chuck DeCroix, Dr. Stanley

Sides, and John MacGregor.

Moccasins, discovered in Salt Cave (now part of Mammoth Cave), 1926.

Kentucky Museum.

"Gothic Chapel" by Charles Waldack, 1866.

Courtesy WKU Library Special Collections.

"Bacon Chamber" by Charles Waldack, 1866.

This chamber is named due to projections from the roof resembling bacon.

Courtesy WKU Library Special Collections.

Report by Alonzo W. Pond about the finding of a mummy in Mammoth Cave, 1935.

Courtesy WKU Library Special Collections.

Map of Mammoth Cave, 1811.

Courtesy WKU Library Special Collections.

The Flint Mammoth Cave System Map.

Featured in the 1975 report by the Cave Research Foundation.

Courtesy Library of Congress.

Historic entrance to Mammoth Cave Saltpeter Works.

Courtesy Library of Congress.

Dr. Rick Toomey and Dr. Chris Groves speak with participants during a trip to Mammoth Cave.

Courtesy Crawford Hydrology Lab.

Cover for a research symposium held at Mammoth Cave in 2016.

Courtesy WKU Library Special Collections.

Scenes from Mammoth Cave, featured in Picturesque America, 1873.

Reproduction courtesy Department of Library Special Collections.

These historical illustrations of Mammoth Cave are similar to others of the period from Europe's

classical Mediterranean karst, which were drawn by founders of karst geology and geographic

studies, Édouard-Alfred Martel and Jovan Cvijić. As scientists, they aimed to acquaint the wider

public with fascinating underground features and to invite others to join them in further

discoveries. Overall the relatively realistic scenes are remarkable as the artists not only had no

proper cameras, but not even lights except for torches.

by Zoran Stevanovic

A current leader of the International Association of Hydrogeologists Karst Commission, Zoran is a

geologist and Professor of the University of Belgrade, Serbia and Chair of the Centre for Karst

Hydrogeology there.

Both tourists and scientists share a common motivation: curiosity. The torch displays point out

how big and endless the passages seem, which geologists seek to explain. Both are motivated by

a sense of wonder and thrill of discovery.

Certain aspects of the cave have been exaggerated. In reality, there is no overhang of the ledge in

the center - it's been added for impact. The "coffin" in the lower-right has been purposely

reshaped to look like a coffin, rather than its real high, narrow, ship-like appearance.

These illustrations are adjusted for maximum impact - to show the cave is an exciting place.

by Art and Peggy Palmer

From their base at the State University of New York at Oneonta, Art and Peggy have been

exploring, studying, and writing about the geology of Mammoth Cave (and many others) for

nearly the last 50 years.

"American Sketches: Mammoth Cave - The Gothic Gallery."

Courtesy Department of Library Special Collections.

Three brave cave explorers are observing the great variety of cave features. A hanging

"stone forest" reminds them of rolling grey clouds on a cave ceiling. Many big and irregular

"stone columns" are connecting the ceiling and floor. In the lower right corner, some

collapsed rocks look like creeping sheep. Like the milk of Mammoths, water with white

contents flows from the top to the bottom. During the dripping, stalagmites and stalactites

grow gradually. It is strong dripping water that flows along in the same way for a long period

that forms the stone columns.

by Pu Junbing

Jungbing is Hydrogeologist and a Professor at the Institute of Karst Geology in Guilin China,

within the Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences. He conducts research throughout

southwest China's karst areas.

Looking at this sketch, I am reminded that both Gothic architecture and karst groundwater

are lacking in this part of Mammoth Cave. Here, Gothic was implied by creating a name based

on some general similarity - the pointed arches of Gothic style. Groundwater was shown by

converting speleothem shapes into something that reminds us of waves on the water surface.

A happy end was inevitable: visitors accompanied by the painter surely appeared back above

ground better stocked by drinks, underground stream water was found in Mammoth Cave in

1838, and Classicism flourished in my country, accompanied by Gothic Revival in North America.

And groundwater was everywhere!

by Peter Malik

Living in a small country, but one blessed with beautiful and fantastic landscapes, Peter is

Department Head for Hydrogeology at Slovakia's national Geological Survey.

Poster for the Eighth Annual Congress of Speleology at Mammoth Dome.

Courtesy Department of Library Special Collections.

It is still very difficult, to this day, to accurately portray a scene in a cave. In 1876, the artist

made a superb job in representing this section of Mammoth Cave. I can see that the wall in the

right seems to comprise collapsed blocks (we call it breakdown). The wall in the left is smooth,

characteristic of being subject to water flow (dissolution by an underground river). The ceiling

cannot be seen, the passage is very high and narrow, suggesting that there was (or is) a water

source that comes from above. We call it a dome.

by Augusto Auler

Since completing graduate studies in the US and Europe, Augusto has been Director of Brazil's

Institute of Karst Geology. Its mission is to study and preserve Brazilian karst areas.

"Echo River" by Grace Kirby Wiley, oil paint on canvas.

Kentucky Museum.

This delightful painting of a boating expedition on Echo River highlights the mystery and thrill of

the world underground.

What happens in that darkness at the end of the river passage? Artists and scientists alike will first

imagine, and then will be compelled to explore this in their differing ways.

by Derek Ford

Derek bicycled some 20 miles through English countryside as a 12-year-old to visit his first caves.

In a world-class karst program at Canada's McMaster University, Derek has by now mentored

many of the world's top cave scientists.

Kettle used to mine saltpeter at

Mammoth Cave during the War of 1812.

Kentucky Museum.

Skeleton of a big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus)

Prepared by Steve Huskey, Ph.D.

Functional Morphology, Department of Biology, WKU.

A solitary roosting bat in Mammoth Cave.

Courtesy National Park Service.

The Usefulness of Echolocation in Bats

By Sam Allen, Fall 2019.

There are a lot of mysteries surrounding bats due mostly for the fact they are nocturnal, and

many people choose to stay clear of them. Bats have great vision especially during low light

conditions, such as the early morning and dusk. During peak nighttime hours they rely mainly on

echolocation and vibrations off from things to locate their prey. Their eyes are a main focus of

the bat, as they are small but very sensitive and can “see” in near pitch-black conditions.

Illustrations by Julie Schuck, WKU art instructor, Fall 2019.

Scenes from Mammoth Cave, featured in Picturesque America, 1873.

Reproduction courtesy Department of Library Special Collections.

These historical illustrations of Mammoth Cave are similar to others of the period from Europe's

classical Mediterranean karst, which were drawn by founders of karst geology and geographic

studies, Édouard-Alfred Martel and Jovan Cvijić. As scientists, they aimed to acquaint the wider

public with fascinating underground features and to invite others to join them in further

discoveries. Overall the relatively realistic scenes are remarkable as the artists not only had no

proper cameras, but not even lights except for torches.

by Zoran Stevanovic

A current leader of the International Association of Hydrogeologists Karst Commission, Zoran is a

geologist and Professor of the University of Belgrade, Serbia and Chair of the Centre for Karst

Hydrogeology there.

Both tourists and scientists share a common motivation: curiosity. The torch displays point out

how big and endless the passages seem, which geologists seek to explain. Both are motivated by

a sense of wonder and thrill of discovery.

Certain aspects of the cave have been exaggerated. In reality, there is no overhang of the ledge in

the center - it's been added for impact. The "coffin" in the lower-right has been purposely

reshaped to look like a coffin, rather than its real high, narrow, ship-like appearance.

These illustrations are adjusted for maximum impact - to show the cave is an exciting place.

by Art and Peggy Palmer

From their base at the State University of New York at Oneonta, Art and Peggy have been

exploring, studying, and writing about the geology of Mammoth Cave (and many others) for

nearly the last 50 years.

Poster for the Eighth Annual Congress of Speleology at Mammoth Dome.

Courtesy Department of Library Special Collections.

It is still very difficult, to this day, to accurately portray a scene in a cave. In 1876, the artist

made a superb job in representing this section of Mammoth Cave. I can see that the wall in the

right seems to comprise collapsed blocks (we call it breakdown). The wall in the left is smooth,

characteristic of being subject to water flow (dissolution by an underground river). The ceiling

cannot be seen, the passage is very high and narrow, suggesting that there was (or is) a water

source that comes from above. We call it a dome.

by Augusto Auler

Since completing graduate studies in the US and Europe, Augusto has been Director of Brazil's

Institute of Karst Geology. Its mission is to study and preserve Brazilian karst areas.

"American Sketches: Mammoth Cave - The Gothic Gallery."

Courtesy Department of Library Special Collections.

Three brave cave explorers are observing the great variety of cave features. A hanging

"stone forest" reminds them of rolling grey clouds on a cave ceiling. Many big and irregular

"stone columns" are connecting the ceiling and floor. In the lower right corner, some

collapsed rocks look like creeping sheep. Like the milk of Mammoths, water with white

contents flows from the top to the bottom. During the dripping, stalagmites and stalactites

grow gradually. It is strong dripping water that flows along in the same way for a long period

that forms the stone columns.

by Pu Junbing

Jungbing is Hydrogeologist and a Professor at the Institute of Karst Geology in Guilin China,

within the Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences. He conducts research throughout

southwest China's karst areas.

Looking at this sketch, I am reminded that both Gothic architecture and karst groundwater

are lacking in this part of Mammoth Cave. Here, Gothic was implied by creating a name based

on some general similarity - the pointed arches of Gothic style. Groundwater was shown by

converting speleothem shapes into something that reminds us of waves on the water surface.

A happy end was inevitable: visitors accompanied by the painter surely appeared back above

ground better stocked by drinks, underground stream water was found in Mammoth Cave in

1838, and Classicism flourished in my country, accompanied by Gothic Revival in North America.

And groundwater was everywhere!

by Peter Malik

Living in a small country, but one blessed with beautiful and fantastic landscapes, Peter is

Department Head for Hydrogeology at Slovakia's national Geological Survey.

"Echo River" by Grace Kirby Wiley, oil paint on canvas.

Kentucky Museum.

This delightful painting of a boating expedition on Echo River highlights the mystery and thrill of

the world underground.

What happens in that darkness at the end of the river passage? Artists and scientists alike will first

imagine, and then will be compelled to explore this in their differing ways.

by Derek Ford

Derek bicycled some 20 miles through English countryside as a 12-year-old to visit his first caves.

In a world-class karst program at Canada's McMaster University, Derek has by now mentored

many of the world's top cave scientists.

WKU's baseball team competes in several

games during the 2018-19 season.

Photos courtesy WKU athletics.

Kettle used to mine saltpeter at

Mammoth Cave during the War of 1812.

Kentucky Museum.

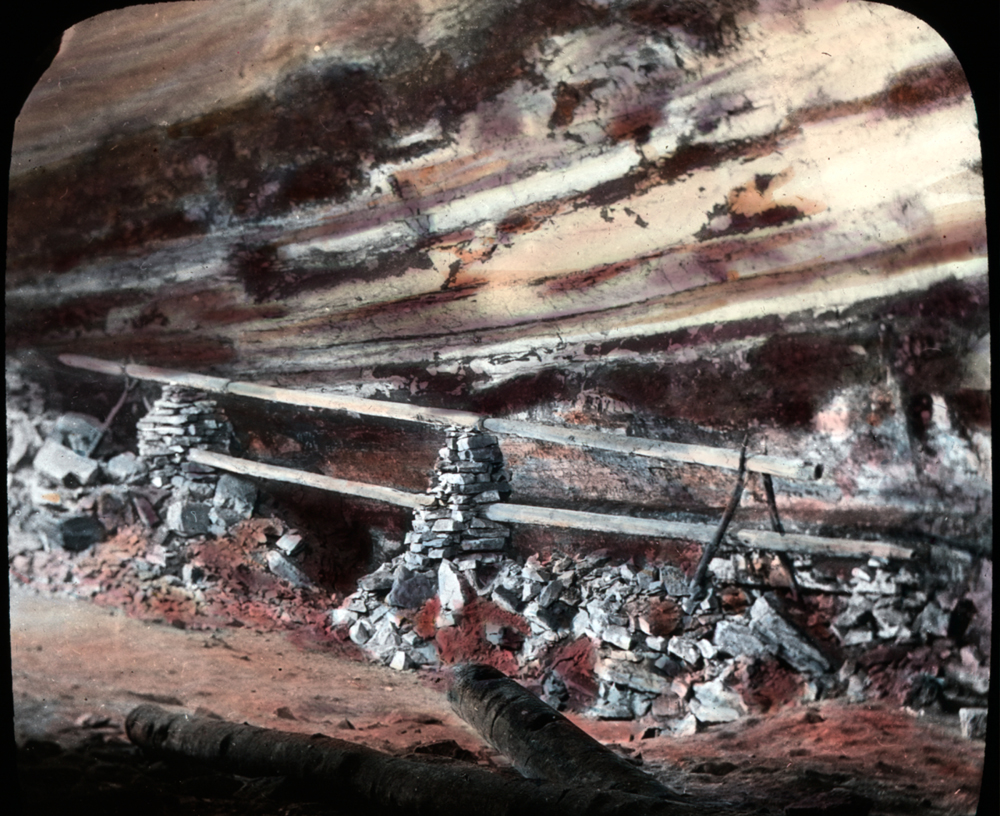

Saltpeter pipes, from glass plate negative by H. C. Ganter and Carlos G. Darnall, 1889.

Courtesy WKU Library and Special Collections.

Tackling Water Quality in the Green River, Mammoth Cave National Park.

by Julie Schuck, WKU art instructor, 2020.

Water quality data charts.

by Julie Schuck, WKU art instructor.

Lee Ann Bledsoe performs experiments on water quality in Crawford Hydrology Lab.

Courtesy Crawford Hydrology Lab.

Students conduct a groundwater tracing experiment.

This waterfall pours off a sandstone layer, then lands on the limestone base

and sinks underground into the cave system.

Courtesy Crawford Hydrology Lab.

Untitled

by Rhiannon Hussung, Architectural Science major, Fall 2019.

Northern red salamander.

Courtesy John MacGregor, Herpetologist, Nongame Program,

Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources.

Cave salamander.

Courtesy Crawford Hydrology Lab.

Marbled salamander eating earthworm.

Courtesy John MacGregor, Herpetologist, Nongame Program,

Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources.

Marbled Salamander

by Savannah Haney, Visual Arts major, Fall 2019.

The /'kra fiSH/: Measurements for the Size of the Species

by Kimberly Jefferson, Advertising major, Fall 2019.

The Marbled Salamander

by Morgan Butler, Visual Arts major, Fall 2019.

Depicts a marbled salamander to scale with a 12-ounce Coke can.

Comparing the two shows how small the salamander is in life.

Jessica Williams places a bag of charcoal into a cave stream for

a groundwater tracing experiment.

Courtesy Crawford Hydrology Lab.

Gastropod Illustration

by Sydney Vest, Visual Arts major, Fall 2019.

This illustrates different gastropods, or snails, showing their different body shapes,

shell shapes, and shell colors.

Corn Snake Stalking its Prey, the White-Footed Mouse

by Kaleb Harness, Visual Arts major, Fall 2019.

Undead at Mammoth Cave: Heterodon platirhinos

by Sophie LaMontagne, Visual Studies major, Fall 2019.

Eastern hognose snakes are named for their stout and upturned noses.

They assume this position to convince predators that they are already dead.

Why are Fawns Often Found Alone?

by Hannah Dunn, Visual Arts major, Fall 2019.

If you see a baby deer resting in the tall grass, leave them alone! Does will often leave

their fawns in a safe place while they graze, returning a few times to nurse. This prevents

attracting predators to the fawn.

Nocturnal

by Meghan Hodges, Visual Arts major, Fall 2019.

Big brown bats are nocturnal, or active at night. These bats are susceptible to white nose syndrome.

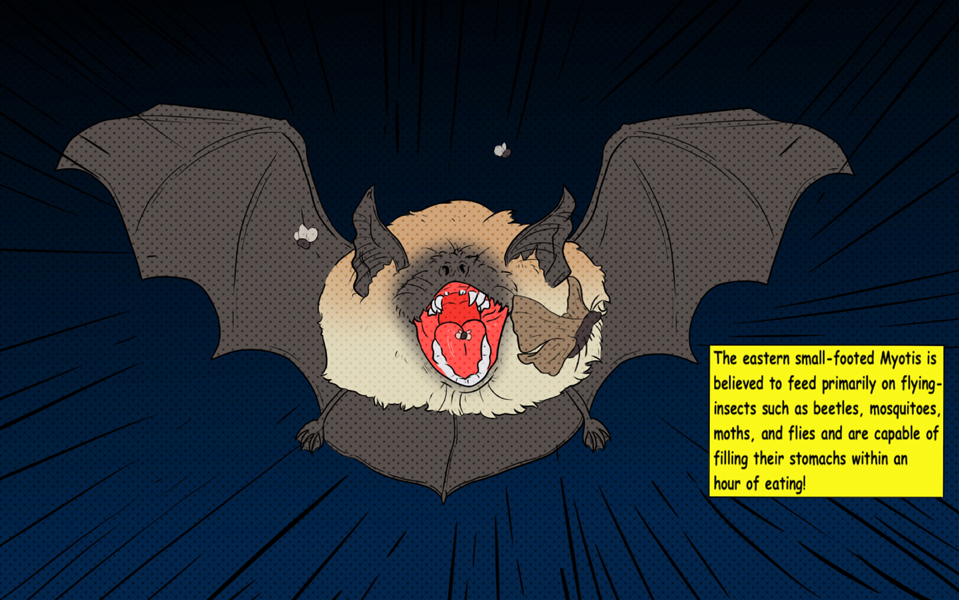

Eastern Small-Footed Myotis's Diet

by Marrick Thurman, Visual Studies major, Fall 2019.

A Significant Salamander

by Maya Dobelstein, Visual Arts major, Fall 2019.

The marbled salamander lives off crickets, earthworms, centipedes, snails, and

numerous small animals.

Kentucky Keep on Shining

by Julie Schuck, WKU art instructor, Fall 2019.

Improvements in air quality and light fixtures reveal a dazzling night sky.

Native

by Sidney Jarboe, Visual Arts major, Fall 2019.

Features native bird species of Mammoth Cave, including the Northern Cardinal,

American Goldfinch, Great Blue Heron, American Redstart, and Belted Kingfisher.

Adult Saw-Whet Owl and Owlet

by Jessie Allison, Elementary Education major, Fall 2019.

These owls are one of the smallest owls, reaching the size of a tomato during adulthood.

This drawing illustrates differences between babies (owlets) and adult owls.

Air quality data chart

by Julie Schuck, WKU art instructor.

Lyla Ross, a 5th grader from University School, assists Park and WKU scientists

with a tracing experiment.

Courtesy Crawford Hydrology Lab.

Tianlong Bridge, a South China Karst natural arch.

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Limestone formations in Furong Cave, within South China Karst.

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Entrance to caves at Puerto-Princesa, 2008.

Courtesy UNESCO.

Outcrop of karst formations at Puerto-Princesa, 2013.

Courtesy Shankar.s via Wikimedia.

Tourist route through Skocjan Caves, April 2013.

Courtesy Lander at Slovenian Wikipedia.

Entrance to Skocjan Caves, 2009.

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Kentucky Cave Shrimp

by Caroline Sadlo, Visual Arts major, Fall 2019.

Speaking for Statistics

by Ashlyn Crawford, Visual Arts major, Fall 2019.

This graphic explores everyday scenes found at Mammoth Cave,

including various wildlife and associated statistics.

Lyla Ross, a 5th grader from University School, assists Park and WKU scientists

with a tracing experiment.

Courtesy Crawford Hydrology Lab.

Autumn Singer presents an exhibit at the American Water Resources

Association Conference.

Courtesy Crawford Hydrology Lab.

Article by Dr. Chris Groves discussing how cave formations reveal

seasonal changes in dripwater flow.

Courtesy Crawford Hydrology Lab.

Limb Regeneration of a Cave Salamander

by Xavier Malies, Visual Studies major, Fall 2019.

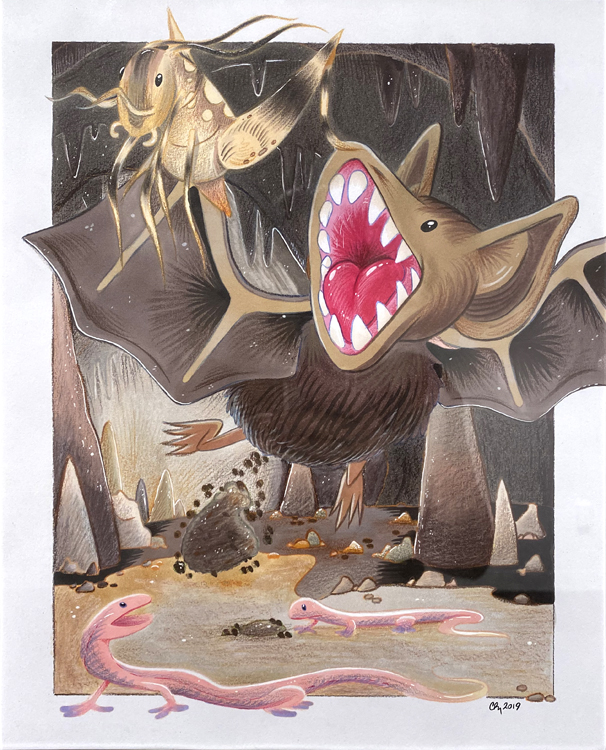

Mammoth Cave Bats

by Kenzie Crowe, Advertising major, Fall 2019.

Students from Bowling Green High School's Science National Honor

Society studying cave formations.

Courtesy Crawford Hydrology Lab.

Mammoth Cave Project

by Allyson Hodge, Fall 2019.

"In the drawing there are five different species of lynx:

1. Lynx rufus floridanus

2. Lynx rufus californicus

3. Lynx rufus (Bobcat)

4. Lynx canadensis

5. Lynx rufus texensis

In the center of the drawing is the Lynx rufus most commonly called the bobcat.

The bobcat can be seen around Mammoth Cave whenever visiting. The lynxes

shown around the bobcat are other types around North America. The point is to

show the difference in the way each cat looks from the other in the face but also

in the markings on their face and the type of fur. Each lynx is from a different

part, making their fur different not just in color but in the patterns they have and

how thick it can be. The Lynx rufus floridanus is from Florida, the Lynx rufus

californicus is from California, the Lynx canadensis is from Canada, and the Lynx

rufus texensis is from Texas. These are all but a few subspecies of Lynx in North

America. There are a lot more, not just in North America, but the whole world."

White Nose Syndrome

by Kayshlyn Cook, Fall 2019.

Kentucky Cave Shrimp

by Liu Yi, Visual Arts major, Fall 2019.

"It shows three Kentucky cave shrimps in my artwork. The Kentucky cave shrimp is

endemic to the Mammoth Cave national park area of Kentucky. It lives only in

underground caves. The Kentucky cave shrimp is nearly transparent. It feeds

mainly on sediments, which are washed into the cave by the flow of groundwater.

The Kentucky cave shrimp also listed as endangered by the state."

Coyote Family

by Tyler Cummins, Visual Studies major, Fall 2019.

"The coyote appears often in the tales and traditions of Native Americans usually

as a very savvy and clever beast. Modern coyotes have displayed their cleverness

by adapting to the changing American landscape. These members of the dog

family once lived primarily in the p[en prairies and deserts, but now roams the

continent’s forests and mountains. They have even colonized cities like Los

Angeles and there over most of in North America. This image shows that the

mother is watching the pups while the father goes hunting. They communicate

with a distinctive call, which at night often develops into a raucous canine chorus."

Gypsum Flowers

by Thy Phan, Visual Arts major, Fall 2019.

Cyanocitta cristata and Clematis versicolor in Mammoth Cave National Park

by Nadya Cournoyer, Advertising major, Fall 2019.

"Blue jays are highly intelligent and adaptable birds. However, with the changing

climate, weather patterns are shifting which is causing birds to change their

behaviors. Researchers have found that many bird species are beginning to spend

the winter further north due to warmer temperatures in the south.

Clematis versicolor (Leather flower clematis) ranges from rocky open woods and

ravines from Kentucky south to Texas. It has a long flowering period lasting from

April to June, resting during the summer and resuming in September/October.

It is important to maintain environments and be aware of climate change for

these species and many others."

The Hoary Bat

by Avery Harlow, Visual Arts major, Fall 2019.

"The hoary bat, one of the many bats found in the Mammoth Cave area, is the

most widespread bat in North and South America. The are one of a few species

that often give birth to twins rather than a single pup. Their fur coloration also

gives them the appearance of being frosted, hence the name “hoary”."

Kentucky Cave Shrimp

by Justine Diedrich, Visual Studies major, Fall 2019.

"I chose to do my Mammoth Cave project according to the eyeless Kentucky cave

shrimp, a particular crustacean species that is only found in Kentucky. The

translucent body and lack of eyes suggest that the crayfish has been developing

underground for many years. When light is pointed toward the crayfish, it’s whole

body seems to glow.

The eyeless cave shrimp mainly lives in large base streams with slow water flow. It

is call the eyeless shrimp because it has adapted to its environment so well that it

has stopped developing eyes altogether It navigates the cave using its antennas

and eats fungi from the floors of the streams."

What Whitetail Deer Eat

by Kelley Clark, Visual Studies major, Fall 2019.

"In the center of my picture is a male whitetail deer. You can tell he is a male

because he has antlers. Whitetail deer’s diet change depending on the season, and

what is available at that time. In the top left corner of the picture is walnuts. In the

top right corner is an ear of corn. In the Bottom right is acorns. The bottom left is

apples."

Chamomile Study

by Lillie Whelchel, Visual Arts major, Fall 2019.

"Mammoth Cave National Park houses many types of plants. This illustration

highlights Chamomile, a common plant here and throughout the world.

Chamomile has white petals, usually 12 of them, and a golden yellow center. My

depiction doesn’t exactly replicate the colors of Chamomile, as I only used a

single color. Chamomile is sought after for its appealing fragrance and its

medicinal properties. Chamomile is also an herb that is commonly used in teas."

Cave Salamander

by Sarah Terry, Visual Arts major, Fall 2019.

"Mammoth Cave National Park is home to a variety of life. One amphibious life

form is the Cave Salamander. Despite its name, Eurycea lucifuga is not restricted

to caves, but can also be found near bluffs, rocky walls, and under damp logs.

Inside caves, however, they are typically found in the “twilight zone” of the cave,

an area just inside the cave’s entrance where there is some light, but not enough

for plants to grow. These salamanders typically have a bright reddish-orange

body heavily marked with black spots and dashes. E. Lucifuga eat many

invertebrates, including many kinds of insects, mites, ticks, isopods, earthworms,

and other soft-bodied creatures. This illustration shows a cave salamander I

between a bed of rocks in Mammoth Cave.

This species is endangered in Kansas but is thriving in Kentucky. Human activities

in and around the caves in addition to groundwater pollution have been though

to be the potential sources of the decline in populations. It is important to

maintain the environment for this species so they may thrive and the ecosystems

which they affect may continue to survive."

Glaucomys Volans (Flying Squirrel)

by Elizabeth Hilbrecht, Visual Studies major, Fall 2019.

"Mammoth Cave National Park is home to many different creatures, one of them

being the Glaucomys volans also known as the flying squirrel. Despite the name,

these squirrels do not actually fly. They glide through the air using their wings

which are a thin layer of skin that is attached to the body, arm, and leg of the

squirrel, almost acting as a parachute for the squirrel. This allows this type of

squirrel to soar around 28 meters in length using their tail to help navigate from

tree to tree throughout the forest."

Scarlet Tanager (Piranga olivacea)

by Erin Taylor, Visual Arts major, Fall 2019.

"The Mammoth Cave National Park is a sanctuary to many species of plants, trees,

and ground dwellers. They are home to about 200 different species of birds as

well. Many of them are migratory birds in which we see at least twice a year—one

being the scarlet tanager. This illustration provides detail about this specific bird

and its life cycle.

1. Scarlet Tanager ID

2. Breeding/Migration

3. Nesting

4. Diet

The biggest threat to their population is habitat encroachment. This is due to

road construction or land clearing for human expansion. But with protected parks

like the Mammoth Cave National Park, these species of bird will continue to thrive."

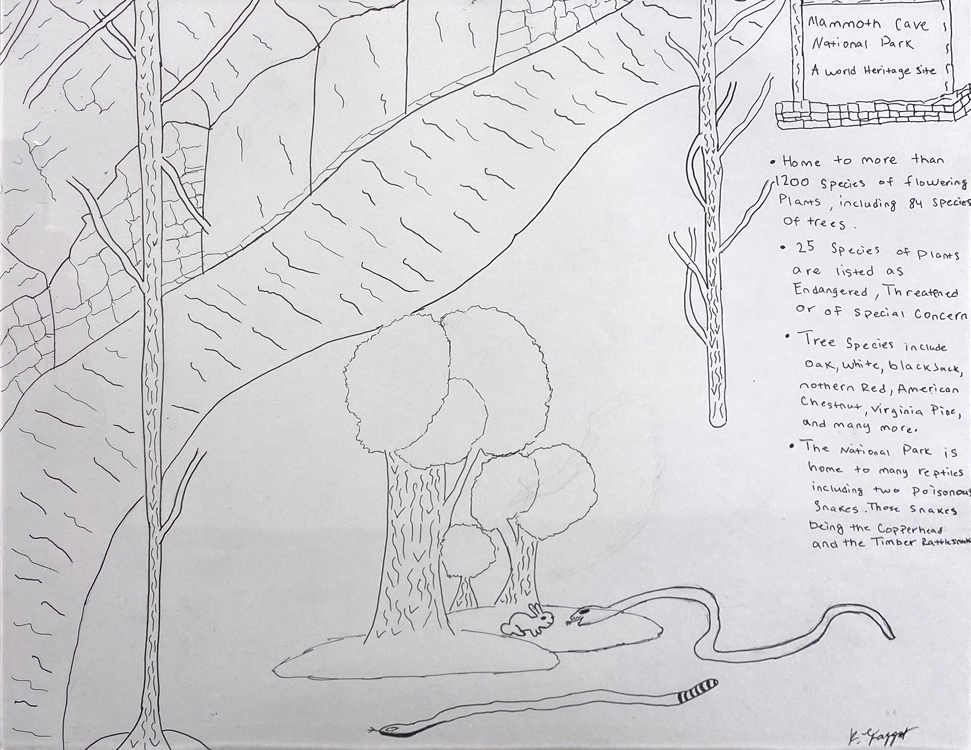

Mammoth Cave National Park: A World Heritage Site

by Kaharie Taggart, Architectural Science major, Fall 2019.

A Silent Tragedy

by JoyBeth Heberly, Visual Arts major, Fall 2019.

"White Nose Syndrome, caused by a fungus known as Pseudogymnoascus

destructans, threatens bat populations in Mammoth Cave, including the Norther

Long Eared Bat. The white fungus thrives in cold, damp areas and appears on

bats’ noses, wings, and ears. The colonization of the fungus on these areas of

bats’ skin is how the syndrome got its name. This syndrome has cause the deaths

of millions of bats by causing bats to wake out of their dormant state, burning

through calories stored for hibernation, resulting in the bats dying of starvation.

Humans are causing a rise in the presence of the fungus by wearing

contaminated caving gear and polluting the cave ecosystem. In order to save bat

populations like the Northern Long Eared Bat and prevent contamination,

humans must be cautious of our effect on the environment around us."

Mammoth Cave Flowers

by Taylor Smith, Fall 2019.

Bats in Mammoth Cave National Park

by Jonathan Batts, Broadcasting major, Fall 2019.

"Mammoth Cave National Park is home to many species of bats, including big

brown bats, little brown bats, tricolored bats, and so on. Most of these bats

inhabit the caves, however, the eastern red bat mostly live above land.

1. Eastern red bat (Lasiurus borealis)

2. Big brown bat (Eptisecus fuscus)

3. Little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus)

4. Tricolroed bat (Perimyotis subflavus)

These bats have inhabited the tunnels of Mammoth Cave for millions of years."

Owl Species in Mammoth Cave National Park

by Emma Moody, History major, Fall 2019.

"Mammoth Cave National Park is home to dozens of predatory birds. Three,

possibly four of which are owls. This illustration includes four species of owls, including:

1. Great Horned Owl, Bubo virginianus, present in the park

2. Eastern Screech Owl, Megascops asio, present in the park

3. Barred Owl, Strix varia, present in the park

4. Northern Saw-whet Owl, Aegolius acadicus, probably present in the par

These incredible animals are incredibly valuable to the ecosystem and need to be

protected because they are part of nature’s pest control team, keeping rodent

populations level and under control."

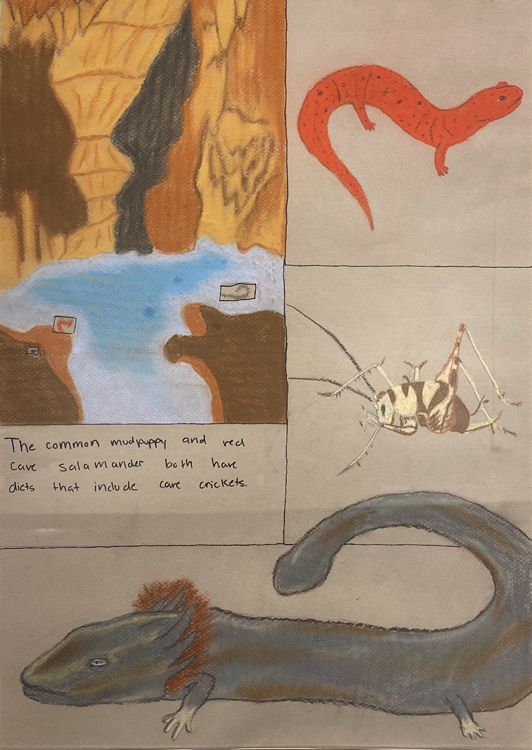

Common Mudpuppy and Cave Salamander

by Nicole Crosby, Visual Arts major, Fall 2019

The Hoary Bat AKA Lasiurus cinereus

by Hunter Garrett, Visual Arts major, Fall 2019.

"Mammoth Cave is home to all kinds of interesting animals. Animals in this habitat

happen to include different species of bat, including Lasiurus cinereus, a bat with

quite a few interesting physical traits. This bat, whose body is covered with fur that

often comes in light and/or grey tones, has the unique ability to swoop down to

capture its prey without making a sound. This can be a very useful tactic, especially

when it flies through its deep, dark cave home, looking for insincts like moths for its

diet. I believe this bar to be a standout among the creatures living in Mammoth

Cave, and it is my privilege to share this interest of mine with the rest of WKU and beyond."

Stephen Bishop, Mammoth Cave Explorer

by Hailey Bossert, Advertising major, Fall 2019.

The Food Chain of Mammoth Cave

by Clayton Roederer, Visual Studies major, Fall 2019.

"While it was one much greater, Mammoth Cave is presently home to a modest

ecosystem of bats, such as the Little Brown Bat (Myotis lucifugus). Like most bats,

Little Brown Bats are insectivores. In the case of Mammoth Cave, this diet is

mostly satisfied with the cave cricket, or Rhaphidophoridea. The bats give back to

the ecosystem in their feces, which is one of the main dietary staples of the

Grotto Salamander (Eurycea spelaeus)."

Ed Bishop; Follow His Footsteps

by Kristen Kendrick-Worman, Fall 2019.

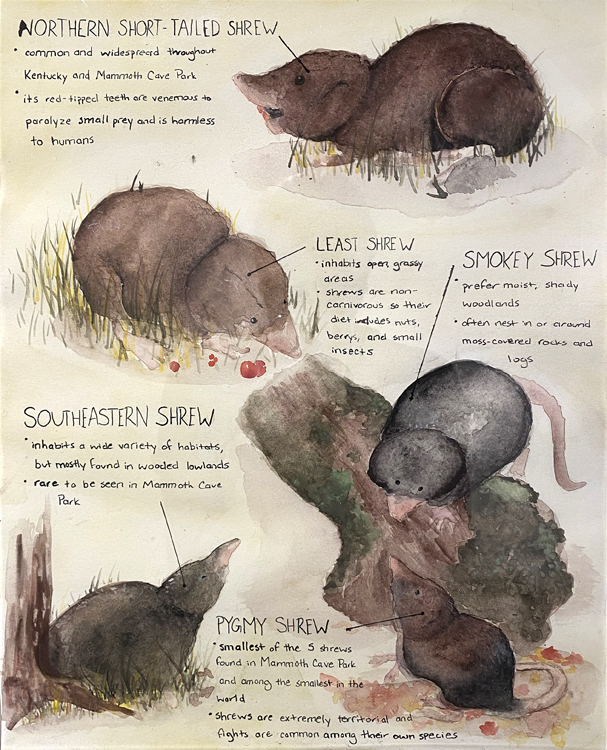

Shrews of Mammoth Cave

by Sarah Wolf, Visual Arts major, Fall 2019.

Click here to view in a new window.

HAD Artist Collective Murals

HAD Artist Collective Murals

In early 2018, the WKU Department of Art welcomed

members of the HAD Artist Collective from Visoko, Bosnia

and Herzegovina. As part of the International Years Of (IYO)

Bosnia and Herzegovina, these visiting artists provided mural

workshops for WKU students and the wider Bowling Green

community. Workshop participants had the opportunity to

observe the artists' unique wall cut process and assist in the

creation of the two murals you see here on either side of the

Kentucky Museum courtyard. The culmination of the visit was

a mural unveiling that took place on Friday, March 2nd, 2018.

HAD Collective artists Muhamed Bešlagić (Hamo), Anel Lepić,

and Damir Sarač grew up during the Bosnian War and, in

2015, came together to make artwork about Bosnia's past and

future. According to the Collective, "making already forgotten

human beings alive, visible, and important to everybody else is

what we intend to achieve with our artwork. We use all kinds

of hard surfaces, mainly walls – we scratch, carve, and engrave

wall layers to achieve depth and create the form of a human

portrait, often choosing everyday people from all sides of the

world." Using hammers, chisels, drills, and found paint, HAD

transforms abandoned buildings in the landscape of Bosnia

into sites for remembrance.

HAD Collective's visit was sponsored by the WKU

Department of Art, Potter College of Arts and Letters, the

Office of the International Programs, the Kentucky Museum,

and a SpiritFunder campaign.

Click here to view in a new window.

Whitework: Women Stitching Identity

Conservation

Repair & Stabilization

Cleaning

Why White?

Continuing White Threads

Conservation

Repair & Stabilization

Cleaning

Why White?

Continuing White Threads

Conservation

Repair & Stabilization

Cleaning

Why White?

Continuing White Threads

Flax wheel

Cotton gin

Wholecloth quilt, ca. 1805

Hand-woven "Marseilles" quilt, 1790-1820

Embroidered counterpane, ca. 1810

Weft-loop woven counterpane, ca. 1804

Flax wheel

Women on the American frontier typically used several types of spinning wheels in the home production of textiles, including

Saxony-type wheels such as this one. The linen thread produced by flax wheels was used to weave textiles or combined with

cotton or wool to make a variety of textiles and clothing. Often celebrated as tangible reminders of our colonial or pioneer history,

the number of surviving wheels is an indication of the value the original owners and their descendants placed on them.

KM 833

Cotton gin

Although Kentucky’s climate made large scale production of cotton unsuitable, many farmers grew it for in-home

production of textiles. To expedite the time-consuming task of removing seeds, some Kentuckians made their own version of

Eli Whitney’s cotton gin, such as the example on exhibit. Women were often tasked with the responsibility for carding the

cotton, spinning the resulting fiber into thread, and weaving it into cloth. Even after manufactured cloth was readily available

for purchase, some women continued to raise small plots of cotton, often for use as batts in their quilts. Oral histories record

this practice continuing well into the 20th century.

1976.22.1

Wholecloth quilt, ca. 1805

Rebecca Smith Washington (1786—1861)

Cotton/flax blend

Rebecca Smith’s hand-quilted bedcover is a rare surviving example of the influence of imported British woven quilts.

Her exquisitely stitched motifs mimic the framed-center format, intricate floral details, and filled background pattern of the popular

manufactured textiles. The quilt reportedly “took seven years to stitch.” Rebecca Smith was born in Virginia and married Whiting

Washington, a nephew of George Washington. The couple moved to Russellville, Logan County, where they raised their family.

Kentucky Museum, 2652

Hand-woven "Marseilles" quilt, 1790-1820

Unknown professional weaver

Cotton/flax blend

Factories throughout England produced fancy bedcovers on specialized looms from American-grown cotton. The finished

products, described as “quilted in the loom,” were among the popular British textiles exported to the United States as

fashionable consumer goods. In the years leading up to the War of 1812, patriotic women expressed support for an

embargo against British textiles by creating their own embellished bedcovers.

Kentucky Museum, 1961.1.6

Embroidered counterpane, ca. 1810

Elizabeth “Betsy” Patton Toomey

Warp: flax; Weft and embroidery yarns: cotton/flax blend

Elizabeth Patton Toomey was the granddaughter of Matthew Patton, who emigrated from Ireland, first to Virginia and then

to Clark County, Kentucky. Her mother died soon after her birth, and “Betsy” was raised by her aunt, Elizabeth Yeager

Patton. Betsy’s counterpane includes Dresden work, which indicates that she learned embroidery at a female

academy. The design of her counterpane closely resembles two others, pointing to a single unidentified instructor.

Kentucky Historical Society, 1981.11

Weft-loop woven counterpane, ca. 1804

Elizabeth O’Neal (1786-1891)

Warp: flax; Wefts: cotton/flax blend

Elizabeth O’Neal was born in present-day Nelson County, Kentucky, in 1786. Her mother, Fannie Hall, was a weaver

whose parents had emigrated from West Yorkshire, England, to Fairfax, Virginia, around 1750. Elizabeth learned to weave

from her mother. In 1804, she wove this white counterpane in a traditional English weft-loop style which predated the

more complex Bolton counterpanes woven in neighboring Lancashire.

Kentucky Museum, KM 2021.2.1

Flax wheel

Cotton gin

Wholecloth quilt, ca. 1805

Hand-woven "Marseilles" quilt, 1790-1820

Embroidered counterpane, ca. 1810

Flax wheel

Women on the American frontier typically used several types of spinning wheels in the home production of textiles, including

Saxony-type wheels such as this one. The linen thread produced by flax wheels was used to weave textiles or combined with

cotton or wool to make a variety of textiles and clothing. Often celebrated as tangible reminders of our colonial or pioneer history,

the number of surviving wheels is an indication of the value the original owners and their descendants placed on them.

KM 833

Cotton gin

Although Kentucky’s climate made large scale production of cotton unsuitable, many farmers grew it for in-home

production of textiles. To expedite the time-consuming task of removing seeds, some Kentuckians made their own version of

Eli Whitney’s cotton gin, such as the example on exhibit. Women were often tasked with the responsibility for carding the

cotton, spinning the resulting fiber into thread, and weaving it into cloth. Even after manufactured cloth was readily available

for purchase, some women continued to raise small plots of cotton, often for use as batts in their quilts. Oral histories record

this practice continuing well into the 20th century.

1976.22.1

Wholecloth quilt, ca. 1805

Rebecca Smith Washington (1786—1861)

Cotton/flax blend

Rebecca Smith’s hand-quilted bedcover is a rare surviving example of the influence of imported British woven quilts.

Her exquisitely stitched motifs mimic the framed-center format, intricate floral details, and filled background pattern of the popular

manufactured textiles. The quilt reportedly “took seven years to stitch.” Rebecca Smith was born in Virginia and married Whiting

Washington, a nephew of George Washington. The couple moved to Russellville, Logan County, where they raised their family.

Kentucky Museum, 2652

Hand-woven "Marseilles" quilt, 1790-1820

Unknown professional weaver

Cotton/flax blend

Factories throughout England produced fancy bedcovers on specialized looms from American-grown cotton. The finished

products, described as “quilted in the loom,” were among the popular British textiles exported to the United States as

fashionable consumer goods. In the years leading up to the War of 1812, patriotic women expressed support for an

embargo against British textiles by creating their own embellished bedcovers.

Kentucky Museum, 1961.1.6

Embroidered counterpane, ca. 1810

Elizabeth “Betsy” Patton Toomey

Warp: flax; Weft and embroidery yarns: cotton/flax blend

Elizabeth Patton Toomey was the granddaughter of Matthew Patton, who emigrated from Ireland, first to Virginia and then

to Clark County, Kentucky. Her mother died soon after her birth, and “Betsy” was raised by her aunt, Elizabeth Yeager

Patton. Betsy’s counterpane includes Dresden work, which indicates that she learned embroidery at a female

academy. The design of her counterpane closely resembles two others, pointing to a single unidentified instructor.

Kentucky Historical Society, 1981.11

Corded and stuffed quilt, ca. 1800

Weft-loop woven counterpane, 1804

Corded and stuffed quilt, ca. 1800

Temperance Wren Sharp (1783- after 1850)

Temperance Wren married John Sharp in 1816, in Paint Lick, Garrard County, Kentucky. In 1851, her son, William died

at age 25. A month later, his young widow Priscilla gave birth to their daughter, Willia Sharp. Priscilla took the baby to her

father’s home in Mercer County, where grandmother Temperance and her daughter, also named Temperance, reportedly

“used to spend months on visits” to the Brewer home. Willia inherited both her grandmother’s white quilt and her aunt’s

appliqued Rose quilt.

Kentucky Museum, 1806

Weft-loop woven counterpane, ca. 1804

Elizabeth O’Neal (1786-1891)

Warp: flax; Wefts: cotton/flax blend

Elizabeth O’Neal was born in present-day Nelson County, Kentucky, in 1786. Her mother, Fannie Hall, was a weaver

whose parents had emigrated from West Yorkshire, England, to Fairfax, Virginia, around 1750. Elizabeth learned to weave

from her mother. In 1804, she wove this white counterpane in a traditional English weft-loop style which predated the

more complex Bolton counterpanes woven in neighboring Lancashire.

Kentucky Museum, KM 2021.2.1

Corded and stuffed quilt, ca. 1800

Weft-loop woven counterpane, 1804

Corded and stuffed quilt, ca. 1800

Temperance Wren Sharp (1783- after 1850)

Temperance Wren married John Sharp in 1816, in Paint Lick, Garrard County, Kentucky. In 1851, her son, William died

at age 25. A month later, his young widow Priscilla gave birth to their daughter, Willia Sharp. Priscilla took the baby to her

father’s home in Mercer County, where grandmother Temperance and her daughter, also named Temperance, reportedly

“used to spend months on visits” to the Brewer home. Willia inherited both her grandmother’s white quilt and her aunt’s

appliqued Rose quilt.

Kentucky Museum, 1806

Weft-loop woven counterpane, ca. 1804

Elizabeth O’Neal (1786-1891)

Warp: flax; Wefts: cotton/flax blend

Elizabeth O’Neal was born in present-day Nelson County, Kentucky, in 1786. Her mother, Fannie Hall, was a weaver

whose parents had emigrated from West Yorkshire, England, to Fairfax, Virginia, around 1750. Elizabeth learned to weave

from her mother. In 1804, she wove this white counterpane in a traditional English weft-loop style which predated the

more complex Bolton counterpanes woven in neighboring Lancashire.

Kentucky Museum, KM 2021.2.1

Weft-loop woven counterpane, 1800-1820

Cotton & Flax Production

Weft-loop woven counterpane, 1800-1820

Anonymous professional weaver

Cotton/flax blend

This counterpane is woven in the same weft-loop technique as those made in Bolton, Lancashire, England, but the

format and the motifs are quite different. Some Bolton weavers continued to weave counterpanes after emigrating

to the United States, where they modified motifs to suit American consumers.

Kentucky Historical Society, 2014.00.2

Weft-loop woven counterpane, 1800-1820

Cotton & Flax Production

Weft-loop woven counterpane, 1800-1820

Anonymous professional weaver

Cotton/flax blend

This counterpane is woven in the same weft-loop technique as those made in Bolton, Lancashire, England, but the

format and the motifs are quite different. Some Bolton weavers continued to weave counterpanes after emigrating

to the United States, where they modified motifs to suit American consumers.

Kentucky Historical Society, 2014.00.2

Weft-loop woven counterpane, 1800-1820

Cotton & Flax Production

Weft-loop woven counterpane, 1800-1820

Anonymous professional weaver

Cotton/flax blend

This counterpane is woven in the same weft-loop technique as those made in Bolton, Lancashire, England, but the

format and the motifs are quite different. Some Bolton weavers continued to weave counterpanes after emigrating

to the United States, where they modified motifs to suit American consumers.

Kentucky Historical Society, 2014.00.2

Embroidered tufted counterpane, ca. 1795

Bolton counterpane, 1790-1820

Embroidered counterpane, ca. 1790

Embroidered counterpane, ca. 1815

Embroidered tufted counterpane, ca. 1795

Rosannah Fisher (1781-1876)

Cotton/flax blend

Rosannah Fisher was born in Culpeper, Virginia, in 1781. She embroidered her counterpane in a design of tufts on a

handwoven ribbed fabric to reproduce the visual appearance of an imported Bolton counterpane. In 1806, at age 25,

she married Martin Hardin. They raised their nine children on a farm in Mercer County. In 1860, Rosannah was

widowed and her household included an enslaved family, identified in her late husband’s will as “Jim, Judy,

and their children.”

Kentucky Historical Society, 1981.16

Bolton counterpane, 1790—1820

Anonymous British weaver

Cotton/flax blend

This hand-woven counterpane was produced in Bolton, Lancashire, England, from American-grown cotton. One or two

weavers worked a double-wide, two-harness loom to weave a bedcover without a center seam. This example would

have been purchased as a fashionable consumer item, to be handed down as a family heirloom.

Kentucky Museum, 2857